By Stephanie Hood

Successfully managing large-scale service change in the NHS demonstrates perfectly that excellent communications practice is no longer all about shaping perceptions but working with audiences to shape realities together.

You’ll learn:

• Major change requires capacity, capability and dedicated resource

• Co-design is the only way to develop new models of care

• Expectation management is critical to successful outcomes

Managing change means difficult decisions

Why is it we regularly see impassioned crowds outside hospitals waving placards to protect services that we know don’t always consistently meet quality standards, or which are no longer being delivered from the most appropriate place?

Why don’t we see those same committed campaigners outside the offices of commissioners demanding better outcomes?

Despite leaps forward in NHS transparency, people often don’t believe there is anything wrong with the status quo or believe it can all be fixed with additional funding.

There is concern about the unknown. Judgements requiring compromise: which is more important - access and travel times, or quality and safety? People feeling ‘done to’ rather than ‘with’. Cynicism from an inability to implement change quickly and offer confidence in the new.

Political arguments playing out which would be better targeted at politicians than NHS leaders and clinicians.

Staff who think proposals are a criticism of individual performance, rather than an acknowledgement they are delivering the best care they can despite, rather than because of, the way services are designed around them.

Within this context, what can communications professionals do to support and help deliver major service change in the NHS?

Pre-consultation period

Negotiate and acknowledge the communications and engagement resource required as part of the programme set up. Doing it well takes capacity, capability and dedicated resource.

The legal duty to involve and engage is at the fore and you must demonstrate evidence of this. It should be part of ongoing activity but needs focusing on the path ahead.

Be clear on governance

Be in key meetings, understand the politics and judgements, who is making decisions, when and how. Particularly when working across multiple organisational boundaries. Do this formally and informally.

Remember publicly it is all ‘the NHS’; most people don’t readily distinguish between the component parts, but you need to be clear how it fits together.

Hold the mirror up in those meetings and be the voice that promotes the patient, staff, public and stakeholder perspective. Build patient and clinical reference groups into the governance structure.

Create a compelling case for change – and get a mandate for it

People talk of needing to maintain public confidence in current services and a delicate balance is needed.

But how many expectant parents knew there was only a consultant obstetrician on the labour ward for 24% of the week in one of the obstetric-led maternity units that recently needed to make changes?

Who knows national stroke guidelines recommend units see at least 500 stroke patients/year and only one of six sites in a county-wide reorganisation currently does?

We need to be more open about what’s working, what isn’t and what could be done better.

Acknowledge that models from the past may have been overtaken with new evidence about what works.

A robust case for change must be evidence-based, led by and agreed by clinicians. Don’t underestimate how long this can take.

The communicator’s role is to bring the technical document to life. Translate the complex to the simple without losing meaning, paint a clear picture of how things are and how things will be if nothing is done. Focus on what matters to people.

Don’t stop telling the case for change story. Identify and work with stakeholders. Get a mandate for change when all agree the status quo is no longer an option. Without it people can backtrack. (‘It’s too difficult, things aren’t so bad, let’s just stick with how things are’).

Develop a burning ambition

A burning ambition is arguably more powerful than a burning platform.

Coalescing around a shared vision for the future is longer-lasting and more motivating, pulling rather than just pushing people to change.

Engage widely and co-design with clinicians, patients and the public. Communicate the vision clearly, in a way that resonates with different audiences – what’s in it for them?

Draw on existing insights and research, there is usually much available, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel.

A new model of care - the importance of clinical leadership, engagement and co-design

Getting the clinical engagement right is paramount. Clinically-led and evidence-based thinking to design new models of care takes time.

Done best it involves many people (e.g. multi-disciplinary workshops with c100 clinicians from multiple organisations), but recognise the commitment required to do this on top of the day job – evening meetings can work best?

Involve patients and public representatives from the start. Test the thinking then test it again with identified stakeholders. Be able to demonstrate ‘you said, we did’ feedback.

Getting people agreed around a model is an important step forward. At this stage people can be objective - it isn’t yet focused on what services could be where. Communicate progress to wider audiences.

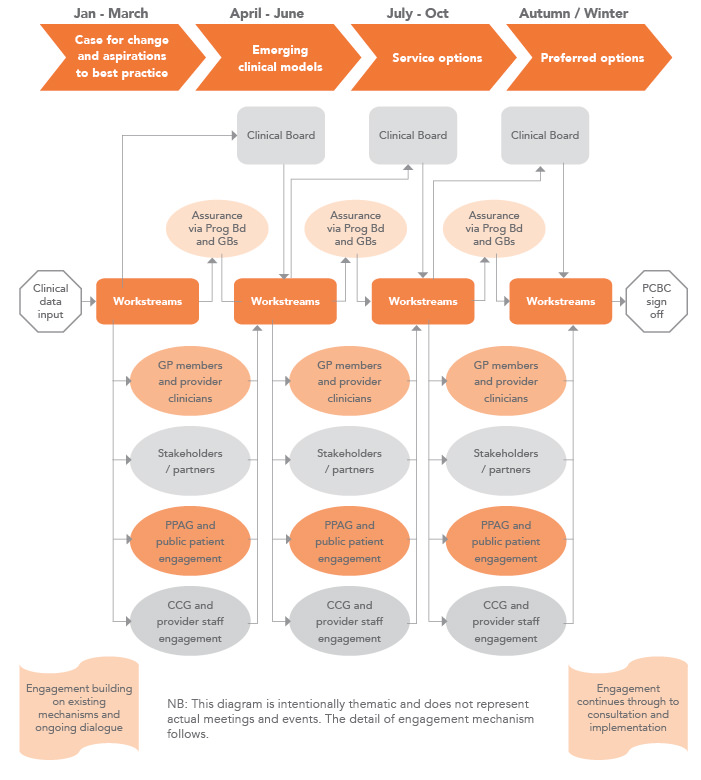

FIGURE 1 Overarching approach: A pre-consultation engagement process

(Timeline has many interdependencies not shown here. Example only and can take many months across each of these stages.)

Developing (and communicating) the options – location, location, location

Engage widely in developing and agreeing the ‘evaluation criteria’ used to assess potential options and agree short-listed options for consultation.

Agreement on the criteria and process (which should include clinician, patient, staff and public representatives) is critical when some people won’t like the outcome.

Communicating the outputs from this stage requires detailed planning and sequenced messaging to all audiences. People will be waiting for the announcement and to understand what it could mean for them.

Be clear these are potential options; no decisions have yet been made.

Assurance, check and challenge

Effective pre-consultation engagement can mean you reach a point where impatience sets in, with demands to ‘get on with it’. But a key stage includes necessary and detailed final assurance with regulators. It is ongoing, but the last stage can take some months.

Keep communicating and planning for consultation and all that entails. There is much to do in demonstrating activity and outcomes from pre-consultation engagement, contributing to the development of the pre-consultation business case, managing multiple stakeholder relations and preparing detailed consultation plans, the consultation document and supporting collateral.

Sign-off processes for communications material flush out previously unidentified differences of opinion and data. You must get this aligned and have a single version of the truth.

Consultation is not a vote

Be clear what you are consulting on and what you are seeking in response – views, feedback, support, concerns, mitigations, additional evidence, alternative solutions – but it is not a vote.

Manage expectations. Public meetings are only one strand of your consultation activity. Targeted research (focus groups, polling, surveys); roadshows and outreach work; digital, social and traditional media; staff and stakeholder communications and engagement; correspondence; briefing; and awareness-raising, all have a role.

Take care not to let the most vocal drown out the quieter voices – all need to be heard.

Consultation for large-scale change is resource intensive. Don’t underestimate the communications, engagement, clinical and leadership time and resource required.

Be visibly clinically led and work as a team. You will need emotional and physical resilience, an eye for detail, responsiveness, rapid rebuttal systems to prevent misinformation from others becoming accepted truths and a determination to listen as well as to explain.

It can be relentless. Hold on to the fact that it should lead to improved services and outcomes for patients. If not, why are we doing it?

FIGURE 02 Example consultation activity overview

Activity taking place throughout consultation period

• Supporting materials, survey and information on website and signposted from partner sites

• Weekly topic-specific content shared via existing and partner channels (e.g. website, social media, bulletins / newsletters, staff briefings, etc.)

• Promotion of consultation to and in 3rd party stakeholder organisations’ communications channels

• Presentations to / attendance at key stakeholder meetings / groups

• Information displayed in provider organisations (including staff areas), GP practices, pharmacies, libraries, community centres and other public spaces

• Providing support materials for 3rd party meetings (e.g. animation, consultation documents, FAQs) and speakers where possible

• Proactive outreach to seldom heard and protected characteristic groups and targeted research programme

• Ongoing media, social media and awareness raising activity

• Regular staff and stakeholder engagement and briefings

• Targeted 1-1 stakeholder engagement to generate responses

• Correspondence, briefing and enquiries

Post-consultation phase

Considering the evidence and decision-making

Decision-makers must give thorough and conscientious consideration to the consultation feedback and need to look at all the evidence in the round before deciding the future shape of services. Avoid a communications and engagement void in the months after consultation before decisions are made.

If there is legal challenge the timeline for change can be long and drawn out. Keep communicating and keep people abreast of what’s happening.

Implementation

Wrap the communications and engagement work into business as usual, but keep it going.

Engage on the granular detail of implementation design, communicate early progress, address issues and manage expectations on timescales for delivery.

Develop clear information for patients. Keep staff and stakeholder engagement at the fore. Keep messaging focused on delivering change to improve outcomes and patient care.

If the right decisions have been made, over time those with placards might realise everyone has been pushing for a shared, broader goal around best care.

In my view, better decisions are made when all perspectives – including dissenters and supporters - have been heard, considered and built into the final design of services. Successfully managing large-scale service change in the NHS demonstrates perfectly that excellent communications practice is no longer all about shaping perceptions. It must be about working with audiences to shape realities together.

Stephanie Hood has advised and supported boards, ministers, policy-makers and senior management teams in the NHS with effective and strategic engagement and communications for 25 years. Working with and across different health and local authority organisations, she has led and delivered communications and engagement and public consultations for a number of high profile NHS service change projects across the country and has developed significant experience and expertise in this area. In 2014 Steph founded Hood & Woolf, a consultancy that helps organisations have effective conversations and productive relationships with the people who matter to them and their business. Hood & Woolf are experts in communicating change, helping clients articulate a clear vision, engage with empathy and impact, tell a consistent story and get results.

Twitter: @HoodSlhood

Online: www.hoodwoolf.co.uk